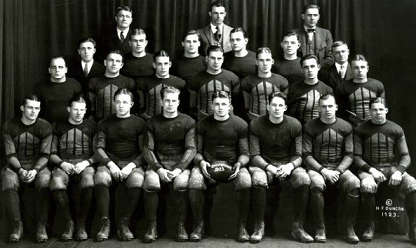

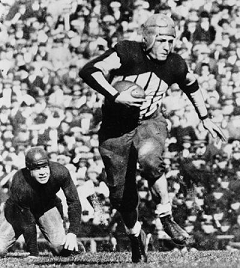

Pictured above is 1923's consensus national champion, 8-0 Illinois, lining up against 7-1 Chicago in the first game played at Illinois' Memorial Stadium. Despite a steady rain, 60,000 fans showed up to watch Illinois win their biggest game of the year 7-0, the legendary Red Grange scoring the touchdown.

However, call me a grinch, but he wouldn't make

However, call me a grinch, but he wouldn't make

This was Cornell's 3rd straight 8-0 season, having been a strong contender for the 1921

This was Cornell's 3rd straight 8-0 season, having been a strong contender for the 1921