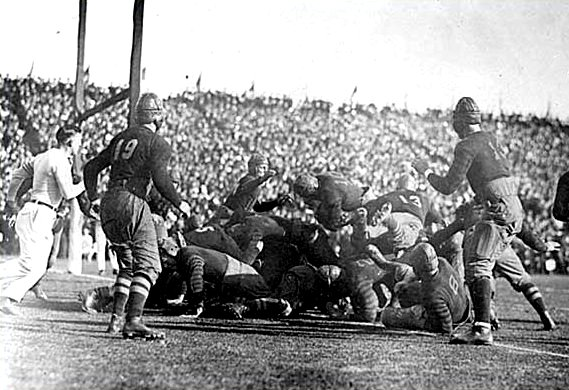

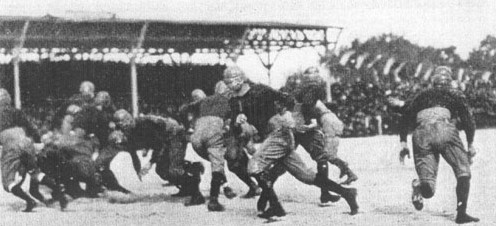

Pictured above is the Harvard touchdown that beat Oregon 7-6 in the Rose Bowl. That put Harvard's record at 9-0-1, a half game better than Penn State's 7-1 in the loss column. Penn State was nevertheless very clearly the consensus choice as Eastern champion amongst Eastern writers in 1919, and in fact Harvard was not considered to be among the top five teams of the East. Decades later, however, when people were selecting national champions for years past, Harvard's 9-0-1 record and Rose Bowl win were presumably all they looked at, and today Harvard is the consensus mythical national champion (MNC) of 1919, while Penn State is not among the 4 teams listed in the NCAA Records Book at all.

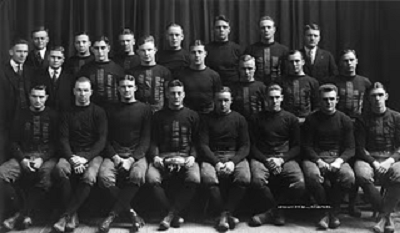

Penn State fielded a pair of strong contenders in 1911 and 1912, but I felt that they came up just short of mythical national championships in both seasons

Penn State fielded a pair of strong contenders in 1911 and 1912, but I felt that they came up just short of mythical national championships in both seasons

Halfback

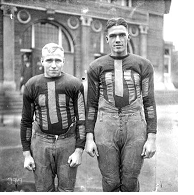

Ed "Dutch" Sternaman, the shorter fellow in the picture to the left,

went on to play pro football for 8 years, and was co-owner of the

Chicago Bears with George Halas. Standing next to him was 6' 1" end

Chuck Carney, a consensus All American in 1920 and a Hall of Famer.

Carney was a great receiver, which proved vital in

the big win at Ohio State, and he was versatile enough that Illinois

was able to use him at center when the need arose. He was also an All

American basketball player.

Halfback

Ed "Dutch" Sternaman, the shorter fellow in the picture to the left,

went on to play pro football for 8 years, and was co-owner of the

Chicago Bears with George Halas. Standing next to him was 6' 1" end

Chuck Carney, a consensus All American in 1920 and a Hall of Famer.

Carney was a great receiver, which proved vital in

the big win at Ohio State, and he was versatile enough that Illinois

was able to use him at center when the need arose. He was also an All

American basketball player.

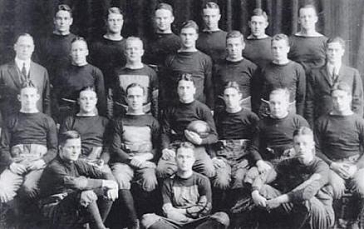

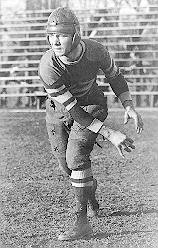

Centre

featured 2 consensus All Americans this season, more than any other

team in the country. The first was their star and captain, Hall of Fame

quarterback Bo McMillin (pictured at left). He was a nonconsensus

AA the next season, and consensus AA again in 1921, when he scored the

32 yard touchdown run that famously beat Harvard 6-0. He was also the

one who had beaten Kentucky 3-0 in 1917, hitting the only field goal he

ever attempted in his career. Because 1918 did not count against

players' eligibility, McMillin started 5 years at Centre. McMillin was

a devout Catholic who did not drink, smoke, or curse, but he was a

prolific and talented gambler, which paid his way through school. He

had little interest in academics, and failed every class his last year

at Centre, so he went into coaching. He beat Harvard again as coach at

Geneva, but he had his most impressive success at lowly Indiana

1934-1947, going 63-48-11 and winning Indiana's first Big 10 title in

1945. Overall, he was 140-77-13 at 4 schools.

Centre

featured 2 consensus All Americans this season, more than any other

team in the country. The first was their star and captain, Hall of Fame

quarterback Bo McMillin (pictured at left). He was a nonconsensus

AA the next season, and consensus AA again in 1921, when he scored the

32 yard touchdown run that famously beat Harvard 6-0. He was also the

one who had beaten Kentucky 3-0 in 1917, hitting the only field goal he

ever attempted in his career. Because 1918 did not count against

players' eligibility, McMillin started 5 years at Centre. McMillin was

a devout Catholic who did not drink, smoke, or curse, but he was a

prolific and talented gambler, which paid his way through school. He

had little interest in academics, and failed every class his last year

at Centre, so he went into coaching. He beat Harvard again as coach at

Geneva, but he had his most impressive success at lowly Indiana

1934-1947, going 63-48-11 and winning Indiana's first Big 10 title in

1945. Overall, he was 140-77-13 at 4 schools.

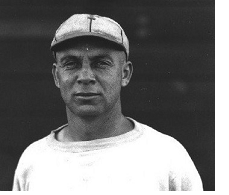

Norwegian-born Knute Rockne (pictured at left) had been a key player on the 7-0

Norwegian-born Knute Rockne (pictured at left) had been a key player on the 7-0  Hall

of Fame halfback and punter George Gipp was Notre Dame's star player

1918-1920. He would be named a consensus All American his senior year,

1920, but he died just 2 weeks after receiving the honor, and in the

process he was transformed from mere mortal to legend. The Vatican has

not yet canonized him, but American culture has, and he has lately

become, according to Notre Dame, "perhaps the greatest all-round player

in college football history." I'm guessing that the "perhaps" is there

for Jim Thorpe, because let's face it, Gipp was not even the best

player of his decade.

Hall

of Fame halfback and punter George Gipp was Notre Dame's star player

1918-1920. He would be named a consensus All American his senior year,

1920, but he died just 2 weeks after receiving the honor, and in the

process he was transformed from mere mortal to legend. The Vatican has

not yet canonized him, but American culture has, and he has lately

become, according to Notre Dame, "perhaps the greatest all-round player

in college football history." I'm guessing that the "perhaps" is there

for Jim Thorpe, because let's face it, Gipp was not even the best

player of his decade.

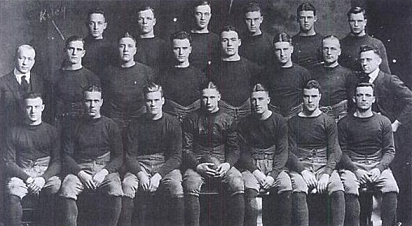

This

was the 6th of 7 straight years that a Southwest team went unbeaten and

untied. Texas A&M had previously taken their turn in 1917, going

8-0, and they were 10-0 in 1919, but in both seasons, the Aggies did

something a little extra

This

was the 6th of 7 straight years that a Southwest team went unbeaten and

untied. Texas A&M had previously taken their turn in 1917, going

8-0, and they were 10-0 in 1919, but in both seasons, the Aggies did

something a little extra